Serving as a missionary in Germany gives one an odd sort of relationship to the Reformation and its commemoration. Like the Second World War, it’s a set of historical events of which visible traces can be found throughout the country and which tends to make people in my own circles – that is, American conservative Reformed Christians – interested in my field. It’s regrettably tempting, in other words, to view the Reformation as a selling point, a convenient way to make my ministry more visible and appealing.

But for all the fun of having been able to pop down to Wittenberg for a day trip while we lived in Berlin, seeing Luther statues dotting the landscape, and the rest of it, I think our first term back in Germany has left me more convinced than I was before that the concerns that drove the Reformation lie at the heart of what the Church absolutely must be doing today, wherever we find ourselves – and at the heart of what I hope our own work will look like for years to come.

I probably have a slightly skewed perspective on how big a deal the 500th anniversary is, based on my social media network, but I’m seeing takes on the Reformation from contemptuous dismissals to breathless rhapsodies. Some focus on the doctrinal formulations around which the Protestants-to-be rallied and their continuing relevance; some agonize over Luther’s venomous anti-Jewish writings and wonder whether they mean the theological movement he started is fatally compromised from the outset. Others are better qualified to sort through all of this; a lot of what’s out there is well worth reading, and all I’d hope to add to the conversation is a more personal reflection.

My own education and experience with the Church, both Stateside and in Germany, and my own feeble efforts at evangelism, have made me more and more passionate about the theme I think is probably as close to the heart of what the Reformation sought to achieve – and actually did, to whatever degree we see it as successful – as anything else: the potency of God’s word.

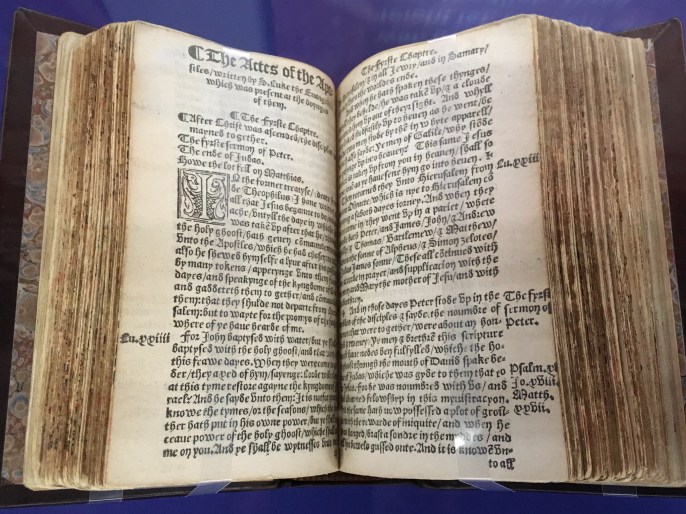

That sounds sort of abstract, maybe. It shouldn’t. It has to do with very simple, fundamental questions: Is God there? If so, has He spoken? If so, what has He said? Luther and those who followed his lead had looked into the Scriptures their Church had always acknowledged as God’s word, and there they had found – or been found by – the living God, the one who (to quote Francis Schaeffer) is there and is not silent. What He said to them in those pages changed them; they knew themselves to have had an encounter with the God their Church claimed to serve but Whose presence it had always obscured in a variety of ways. They were gripped by the conviction that the greatest need of the hour was for the word by which God had made Himself known to be proclaimed, preached, printed, and in all ways placed in the hearts and mouths of the people.

Everything else that came out of the Reformation, I think, flowed from this conviction that no one, not even the Church Christ founded and empowered, has the right either to gainsay God’s word or to refuse its correction – but the flip side of this denial is the passionate insistence that this word is living and life-giving, active and empowering, able to kill and make alive, sent into the world to carry out God’s purpose to be glorified in Jesus Christ forever and ever.

My family and I have been through hard times this year, facing the sudden end of a season of life in which we had been flourishing, and walking through heartrending disappointment and uncertainty. When we were struggling through the worst of the turmoil, I remember the questions that came up in my prayers over and over again: Lord, what do we do? What do you say about this? What we generally mean by questions like these (or at least, what I usually mean) is something like tell me the thing I can do that will make it all better, or, failing that, tell me that I’m in the right! But the voice that speaks in Scripture says: Here is what you can do to honor and obey Me and this is why you can trust Me, why you have a hope that is better than the best possible outcome of this miserable situation, and why these things are true even if you aren’t in the right after all.

I needed to hear these things, and I need to share them with others.

A friend of mine became a Christian in part because he heard Christ’s “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” with fresh ears and realized that this could only be the true and living God speaking. My bit part in his journey to faith was in co-leading a Bible study he participated in several months prior to that moment; none of the others I shared the gospel with in the same way have had the same encounter so far, to my knowledge. Nothing in the life of the Christian is as neat, tidy, or automatic as we might like. But I hope I waver less and less in the certainty that God intends His word to accomplish just what it did in that young man’s heart, and in mine – and that when He is pleased to do great things, the Scriptures written, spoken, learned, understood, and believed are the way He means to do them.

I am an heir of this conviction, one that began to be awakened in the European Church some five centuries ago today, and for that I thank God.

-Ben

That’s beautiful. Thanks Ben.