People don’t mean it badly, but if you’re a missionary for any length of time, you get used to folks’ basic response to seeing you in the USA being something like, “Oh, it’s you! What are you doing here? How long are you around?”

I gather that it’s typical for missions agencies each to have their own jargon for what used to be generally known as “furlough.” That term has the advantage of being a single two-syllable word that means something to most people, something like: these missionaries are back in America, but not because they quit. Also, they may be asking for money.

The language of “furlough” has fallen out of favor, though, because it also gives the false impression that whatever time missionaries spend in their sending country is theirs to spend as they like, that they’re on sabbatical or vacation. Our agency has its own more-or-less proprietary acronym for what we’re doing here: “HMA,” short for “Home Ministry Assignment.” Plenty of ink, virtual or physical, has been spilled to dispel that notion, and articles on missionary blogs or agency sites are probably easy enough to find; my intent here isn’t so much to gain sympathy for missionaries spending time Stateside as to answer some of the FAQs we run into in our particular situation and help give a sense of what the HMA experience is like for us – the good, the bad, and the surreal.

Let me pause to emphasize the phrase our particular situation here: home assignment is a hugely diverse phenomenon, even within our own agency. Different countries have different visa requirements, different ministries lend themselves to different schedules, and missionaries have different needs and life situations. Our particular rhythm is 4-5 years on the field, one full year off. That’s not at all a matter of personal preference – it’s the result of a delightful phenomenon called tax totalization. The long and short of it is that our agency requires us to stay in the US Social Security system, and to do this, the totalization agreement between the USA and Germany says we must leave Germany for a full year before we hit the five-year mark on the field.

That means that our home assignments are very different from a lot of missionaries’. Some spend just a couple of months in the USA, maybe over the summer, every few years. On the plus side, their work on the field suffers reasonably little interruption; on the other hand, the actual time Stateside can be grueling, with visits to different churches every Sunday and as many presentations and meetings as they can squeeze into the time. Their time here is a trip; then they go home to the field.

We’re over on the other end of the spectrum: our field ministry is massively disrupted no less often than every five years. So is our life; our kids miss a year of school, our relationships are long-distance at best, and we have to figure out what to do with our living situation and our stuff for a big chunk of time. It might be subletting or putting everything in storage; either way, we’re saying goodbye to most of our books, kids’ toys, furnishings, and all the little things that make everyday home life what it is.

Then again, once we’ve made it to America, we’re not in quite such a rush. We have some leisure to space out church visits and reports and actually be part of the life of our home church. It’s hard to express just how good that last part is: our churches in Germany are ones we are delighted to support, but while we’re working there, they’re generally church plants, small congregations trying to grow and develop and, a lot of the time, just keep going. The availability of Sunday school classes, Bible studies, moms’ and dads’ groups, prayer groups, reading and study materials, fellowship events, a nursery (!), children’s Christian education, retreats – to say nothing of worship in our heart language and our own theological and liturgical tradition – feels unbelievably luxurious and enriching, especially as it’s not our job to make it all happen.

What is our job while we’re here? Most basically, we’re here to testify to what the Lord has been doing on our field over the past term: it’s edifying to the Church to hear these things, and these kinds of testimonies can be God’s instruments to help call more people into cross-cultural ministry. At the same time, we’re giving an accounting: how have we made use of our supporters’ donations? What kind of a return on their investment can we report? That sort of question may seem crass or unspiritual, but it’s quite the opposite. We’re stewards of gifts offered to God for the sake of His kingdom, and we are answerable for how we manage them.

Part of the job, almost inevitably, is also raising more support. As I’ve written elsewhere, ongoing support almost always trends downward during a term on the field. That’s not necessarily caused by some disaster; it’s just part of life happening while we’re gone. So while we’re here, we need to connect to new people and new churches to put us on firmer financial footing as we head back to the field.

The rest of our time is a mix. On this particular HMA, we’re between church plants, having left our church in eastern Munich self-governing and growing; another plant is in the pipeline at this point, which would involve a move within Munich. That’s quite different from last time around, when we were between cities, preparing to start a whole new range of ministries in a new place. My involvement with our partner seminary isn’t changing, and communication with both faculty and students, grading papers, and so forth is still a regular part of my work week here. With a new team-leader role, oversight of missionary teammates as well as active recruiting are in the mix now as well. As much as possible, we’re trying to prepare ourselves for our return to Germany by seeking continuing-education-type opportunities, preparing teaching material, and attending conferences.

A year is a strange amount of time to be gone. We need to make some kind of a home here in the States, but it needs to be no more difficult to pull up stakes and leave behind than absolutely necessary. We’re torn between the sweetness of time spent with people who know us and share more in common with us than anyone we know in Munich on the one hand, and the longing to be back in a place where we can really invest our time and energy in relationships and ministries we hope to see develop over the long term. The field really is home for our children, and it’s where we’re convinced we’re called to be, where we’ve gained experience, grown spiritually, and found a place where we can serve God’s kingdom.

A veteran missionary once remarked to Anna, “HMA is what kept us going back to the field for all those years.” It maybe sounds harsh, perhaps was even meant harshly, as much as to say: being back in the States always reminded us why we don’t want to live there. There’s something to that. Missionaries can’t ever go home again, not in this life, and we don’t fit here any better than we do on the field, at least after a while. At the same time, HMA is quite literally what keeps us going: it’s our opportunity to keep our family, friends, and churches connected to the people and places we serve the rest of the time. It’s where the giving comes from that allows us to live and share the gospel without burdening the people to whom we’re sent. It’s our chance to remember where we’ve come from and share much of who we are with our children, and it’s a time for God to work on us in ways we trust will bear fruit in Germany for years to come.

-Ben

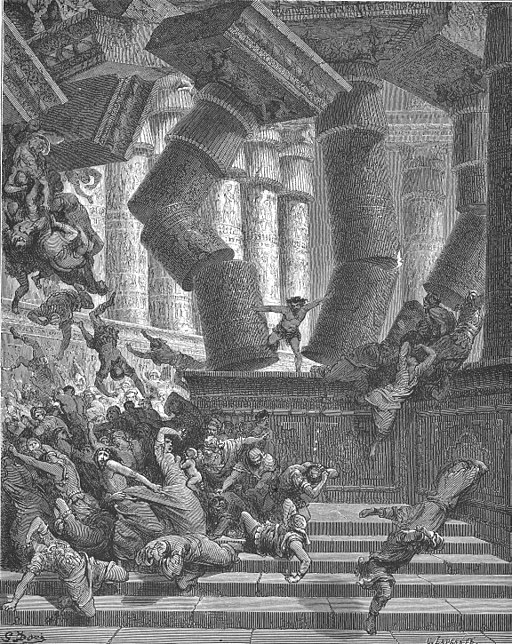

Now Samson embodies his nation fully. Darkness has fallen on a man named Sun (in Hebrew, he’s Shimshon, from shemesh, “sun”), called to be a light. He’s been enslaved, the penalty for his own faithlessness. He’s become a spectacle to the nations. He is Godforsaken, desecrated, weak. His enemies’ attitude is summed up in one detail: they don’t bother with haircuts for their prisoner. Surely, they think, having broken the Nazirite code so definitively, he has forfeited all help from his god.

Now Samson embodies his nation fully. Darkness has fallen on a man named Sun (in Hebrew, he’s Shimshon, from shemesh, “sun”), called to be a light. He’s been enslaved, the penalty for his own faithlessness. He’s become a spectacle to the nations. He is Godforsaken, desecrated, weak. His enemies’ attitude is summed up in one detail: they don’t bother with haircuts for their prisoner. Surely, they think, having broken the Nazirite code so definitively, he has forfeited all help from his god.

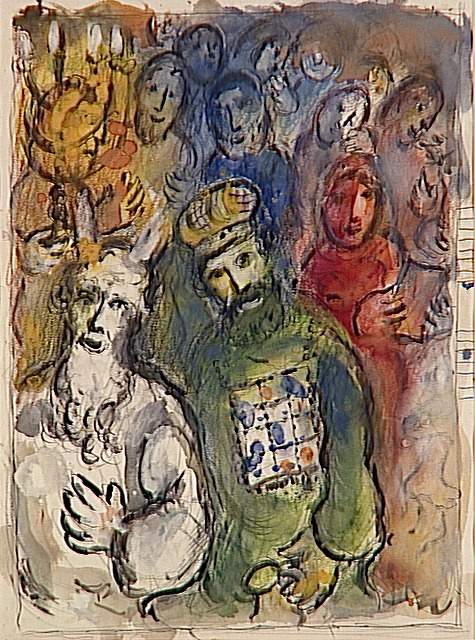

Nevertheless: he will be born with a kingly calling, born to be the Ruler David was on his better days, the morning-light-after-the-rain sort (2 Sam 23:3-4). He will bring the good old days back with him, and better: his coming forth is from of old, from ancient days (Mic 5:2), which is to say, before Abraham was, he is (John 8:58). His “coming forth” is the sallying forth of the Serpent-Crusher, the riding out of the Seed of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to possess the gate of his enemies. Every seemingly forgotten promise is now due to be remembered, a day of reckoning for the God who appears to have so recklessly overcommitted Himself.

Nevertheless: he will be born with a kingly calling, born to be the Ruler David was on his better days, the morning-light-after-the-rain sort (2 Sam 23:3-4). He will bring the good old days back with him, and better: his coming forth is from of old, from ancient days (Mic 5:2), which is to say, before Abraham was, he is (John 8:58). His “coming forth” is the sallying forth of the Serpent-Crusher, the riding out of the Seed of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to possess the gate of his enemies. Every seemingly forgotten promise is now due to be remembered, a day of reckoning for the God who appears to have so recklessly overcommitted Himself. There is going to be a Judge in Jerusalem, one who will bring in the heathen not as instruments of destruction, not as invaders, but as disciples (4:3). The Good Life will be instituted (4:4), everybody having enough, everybody provided the means of rest and enjoyment. Judgment is horrendous news for those liable to it (viz.: you and me and everyone we know), but if judgment falls and there is a future on the other side of it, then the presence of a just judge, the true Judge, means peace.

There is going to be a Judge in Jerusalem, one who will bring in the heathen not as instruments of destruction, not as invaders, but as disciples (4:3). The Good Life will be instituted (4:4), everybody having enough, everybody provided the means of rest and enjoyment. Judgment is horrendous news for those liable to it (viz.: you and me and everyone we know), but if judgment falls and there is a future on the other side of it, then the presence of a just judge, the true Judge, means peace. Before we call the Lord’s coming good news, we had better take some time to audit ourselves. Micah’s harshest words are reserved for the presumptuous, for preachers of and believers in cheap grace (Bonhoeffer’s memorable term). “No, no,” drips the favored rejoinder from languid lips, “don’t be so dramatic.”

Before we call the Lord’s coming good news, we had better take some time to audit ourselves. Micah’s harshest words are reserved for the presumptuous, for preachers of and believers in cheap grace (Bonhoeffer’s memorable term). “No, no,” drips the favored rejoinder from languid lips, “don’t be so dramatic.”